Monica G. Lee, Susanna Loeb, and Carly D. Robinson

What if tutoring didn’t just help students catch up, but also helped them show up?

This study provides compelling evidence that tutoring can do more than boost test scores; it can actually get students back in the classroom. On average, students were 1.2 percentage points less likely to be absent on days when they were scheduled to receive tutoring, suggesting that they are motivated to participate in tutoring. This impact was even greater for middle schoolers and students who’d missed more than 30% of school days the prior year. The study also found that the design matters: tutoring only improved attendance when it combined at least two evidence-based features like small groups, frequent sessions, and in-school delivery.

STUDY CONTEXT AND METHODS

Starting in 2021, the District of Columbia’s Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE) launched a High-Impact Tutoring (HIT) initiative to provide math and ELA tutoring to K–12 students across D.C. In the 2022-23 school year, 4,222 students from 141 schools participated in OSSE-funded tutoring through schools and community hubs, and tutoring was delivered by 38 different providers. The Initiative primarily served students with the greatest academic needs—81% had scored in the bottom two levels on prior year math and ELA assessments. The majority of participants were Black or African American (82%), and 16% were Hispanic.

This study examines how that tutoring affected student attendance during the 2022–23 school year. To make sure their findings were as accurate as possible, the researchers used a method that compares each student to themselves over time. Instead of comparing one student to another, they looked at whether a student was more or less likely to attend school on days when they had tutoring scheduled versus days when they didn’t. This approach accounts for any personal factors that can be correlated with the outcome, like family background or general motivation, and isolates the impact of tutoring on attendance.

The researchers asked:

- Are students more or less likely to be absent on days when they have tutoring, compared to days when they don’t?

- Does tutoring have a bigger impact on attendance for specific groups of students?

- Do certain features of how tutoring is delivered make students more likely to show up to school?

KEY FINDINGS

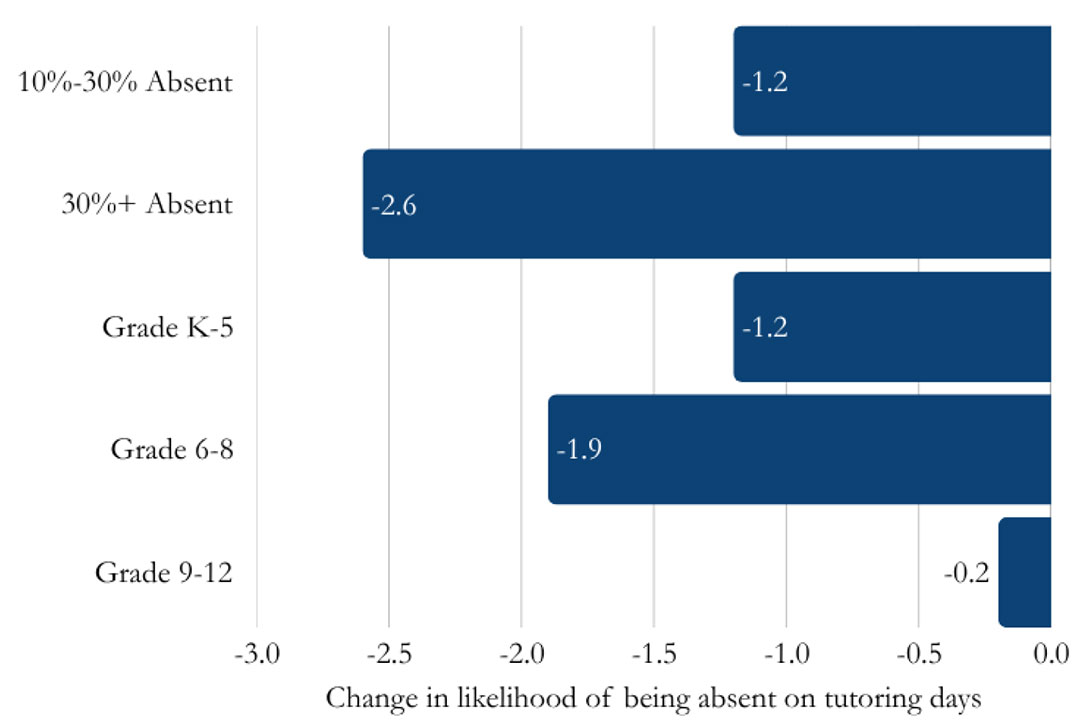

On days when a student is scheduled to receive tutoring, they are 1.2 percentage points less likely to be absent, suggesting that they are motivated to participate in tutoring.

Middle school students benefited the most from having tutoring.

- Middle school students: 1.9 percentage points less likely to be absent on tutoring days.

- Elementary students: 1.2 percentage points less likely to be absent on tutoring days.

- High school students: Little to no change in absence likelihood.

Students who missed 30% or more of school days the prior year saw the largest reduction in absence on tutoring days: 2.6 percentage points. Students with moderate absence (10–30%) and low absence (<10%) also experienced statistically significant, but smaller reductions in absence.

Figure 1: Students who missed 30% or more of school days the prior year and middle school students saw the largest reductions in absences on tutoring days.

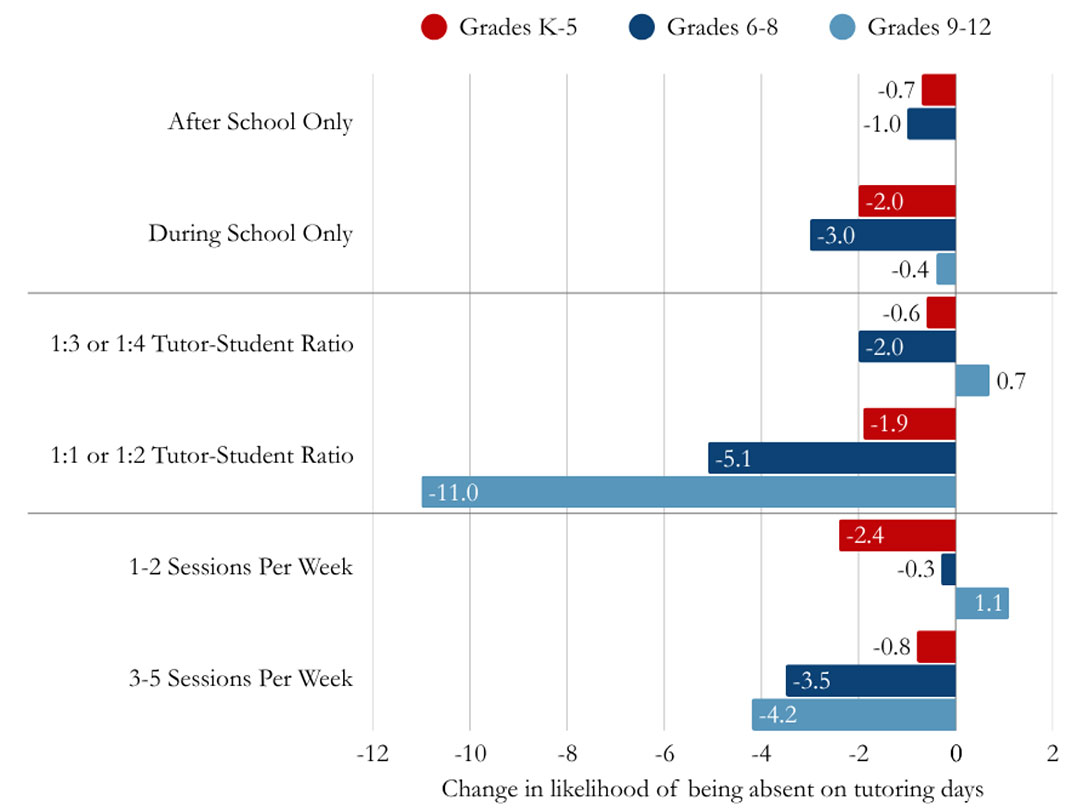

Tutoring had stronger effects when sessions were:

- Held during the school day, compared to after school.

- Tutoring during the school day had a bigger impact than after-school sessions, which suggests it’s not just getting tutoring that helps—having it built into the school day probably makes school feel more supportive and engaging, which in turn helps students show up more.

- Delivered in small groups (1:1 or 1:2 ratios), compared to 1.3 or 1.4 ratios.

- The biggest impact was seen for students who got tutoring in really small groups—just one or two students per tutor—which suggests that getting more personal attention and building a relationship with their tutor might help keep them more motivated.

- Higher frequency (3–5 sessions/week), compared to lower frequency (1–2 sessions/week), particularly for Grades 6–12.

Figure 2: Tutoring had stronger effects when sessions were held during the school day, delivered in small groups, and held with greater frequency.

- Held during the school day, compared to after school.

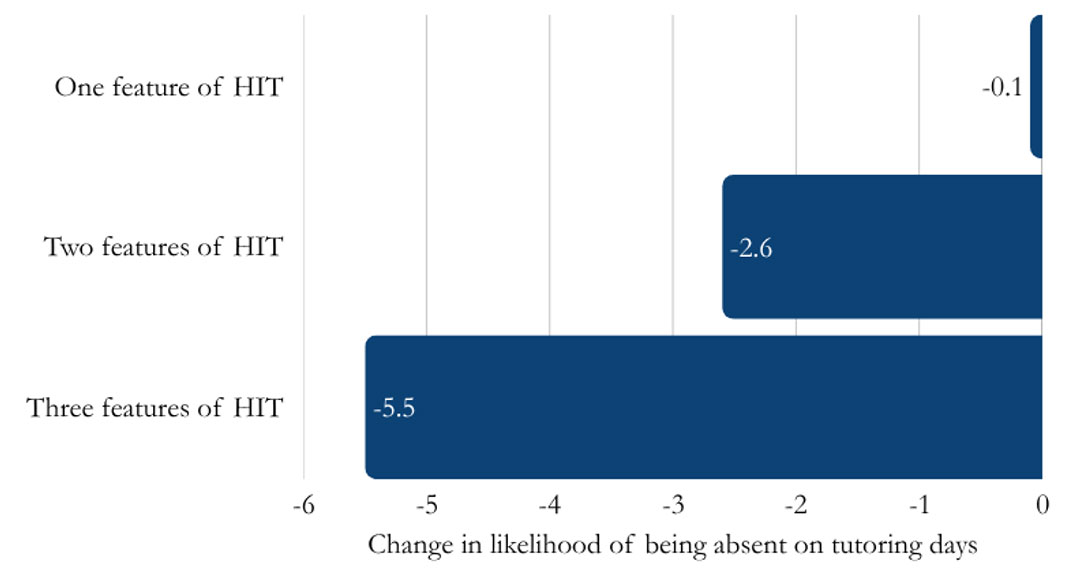

4. Programs need at least two features of high-impact tutoring to be effective.

- None or one feature: Students who received tutoring with none or only one key high-impact feature saw no significant change in their likelihood of being absent.

- Two features: Students who received tutoring with two features were 2.6 percentage points less likely to be absent on tutoring days compared to non-tutoring days.

- All three features: Students who received tutoring with all three features were 5.5 percentage points less likely to be absent on tutoring days compared to non-tutoring days.

Figure 3:Programs need at least two features of high-impact tutoring to be effective.

The features within each “bundle” considered are: Whether the tutoring was offered during the school day; a small tutor-student ratio of 1:1 or 1:2; and 3-5 sessions per week offered by the provider. ‘One feature of HIT’ indicates that the students included within this subgroup analysis attended tutoring programs that contained one of those features while ‘Three features of HIT’ indicates that the students included within this subgroup analysis attended tutoring programs that contained all three of those features.

POLICY AND PRACTICE IMPLICATIONS

Schools and districts can use tutoring to re-engage students at risk of disengagement due to chronic absenteeism. The structure and support provided by tutoring can act as a gentle form of attendance intervention without being punitive.

Programs should target middle school students and chronically absent students. This differential effect is especially important, given that student engagement commonly starts to decline in middle school (Eccles and Roeser, 2011); therefore, expanding tutoring offerings for this age group may be a key priority for future interventions aimed at reducing absenteeism.

Offering any type of tutoring isn’t enough. To drive meaningful improvements in attendance, programs should include at least two high-impact features (e.g., during-school scheduling, small tutor-student ratios, and frequent sessions).

Tutor consistency and relationships seem to matter. Programs should prioritize tutor consistency and training to support both academic and attendance-related outcomes.

To learn more about the OSSE High Impact Tutoring Initiative and the academic impacts, see this report: Implementation of the OSSE High Impact Tutoring Initiative - School Year 2023 – 2024 Second Year Report

FULL WORKING PAPER

This report is based on the EdWorkingPaper “The Impact of High-Impact Tutoring on Student Attendance: Evidence from a State Initiative,” published in June 2025. The full research paper can be found here: https://edworkingpapers.com/ai24-1107

The EdWorkingPapers Policy & Practice Series is designed to bridge the gap between academic research and real-world decision-making. Each installment summarizes a newly released EdWorkingPaper and highlights the most actionable insights for policymakers and education leaders. This summary was written by Christina Claiborne.