Daniel Vargas Castaño, Dareem K. Antoine, and Trey Miller

THE BOTTOM LINE

Making advanced coursework the default, rather than the exception, can transform who gets access.

In Dallas ISD, a simple policy shift of automatically enrolling qualifying students in Algebra 1 resulted in a 13 percentage point increase in enrollment before high school, with particularly strong gains for Hispanic students.

In 2019, the district moved from an “opt-in” to an “opt-out” system, automatically enrolling qualified 5th-grade students in advanced 6th-grade courses, shifting from an opt-in system that often relied on family or teacher advocacy. The results show that when schools remove hidden hurdles, more students, particularly those often left out, get on a path to rigorous coursework and greater opportunities.

THE POLICY

DISD’s opt-out policy was designed to increase access to advanced coursework by automatically enrolling 5th graders who met state-defined proficiency benchmarks (a Math STAAR 5th grade scaled score above 1625, roughly equivalent to scoring in the top 50% statewide) into advanced 6th-grade classes. Families could still choose to opt out, but the default was placement into the “Advanced Pathway,” which would lead to Algebra I in 8th grade. If students were not placed in the “Advanced Pathway,” they were on a trajectory that would lead to Algebra I in 9th grade instead.

The goals of the policy included:

- Increase overall enrollment in advanced coursework, particularly Algebra I before high school.

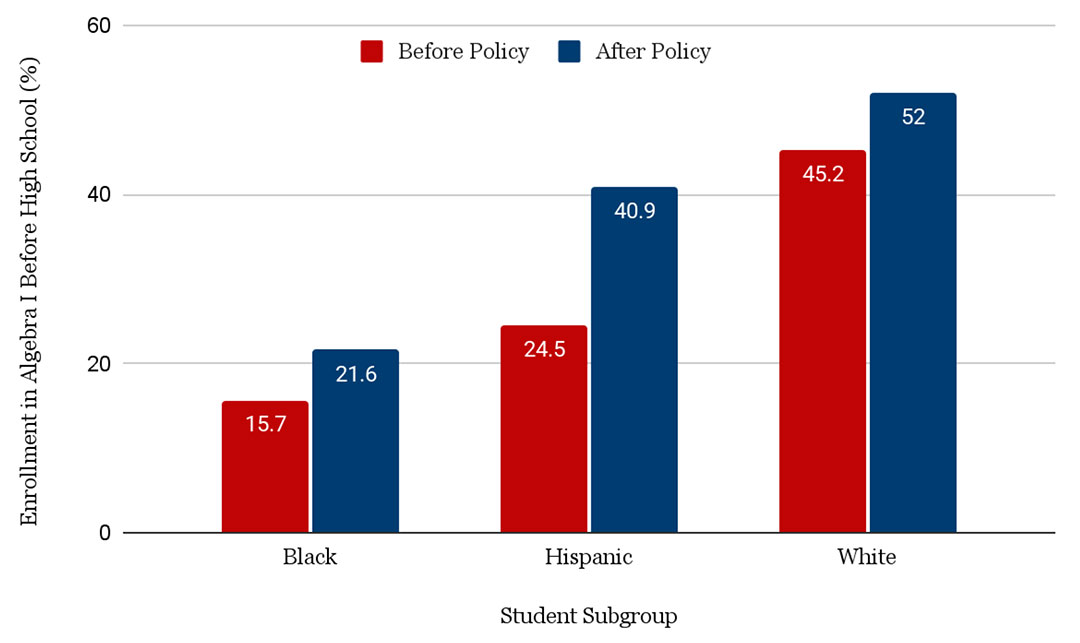

- Reduce disparities in access to advanced classes, especially for Black, Hispanic, and low-income students, who were often underrepresented in honors and pre-AP tracks despite being qualified. Before the policy, only 15.7% of Black students enrolled in Algebra I by 8th grade, compared to 45.2% of White students.

- Create a more equitable and systematic placement process by relying on objective academic criteria rather than recommendations or parent advocacy, which tend to advantage more privileged families.

STUDY DESIGN AND METHODS

The researchers used the Synthetic Control Method (SCM), a generalized version of the Differences-in-Differences (DiD) approach, to estimate the causal effect of the opt-out policy on enrollment in Algebra I by 8th grade. DiD is a quasi-experimental method that compares the change in outcomes before and after a policy in a treated group (in this case, DISD) to the change in outcomes in a control group that did not experience the policy. Instead of comparing DISD to all other districts in Texas, which differ significantly in demographics and size, they created a weighted “synthetic” control group made up of three demographically similar districts (Houston, San Antonio, and Aldine ISDs).

KEY FINDINGS

The opt-out policy led to a substantial increase in advanced math enrollment. Dallas ISD saw a 13 percentage point increase in the share of students taking Algebra I before high school, rising from 23.6% to 37%. This translates to approximately 1,600 more students who took Algebra I in 8th grade because of auto-enrollment. The study used methods that show this increase was caused by the policy, rather than broader trends across Texas districts.

Hispanic students experienced the largest increase in access to Algebra 1 by 8th grade. Enrollment in Algebra I before high school increased by 16.4 percentage points for Hispanic students, compared to 6.8 percentage points for White students. As a result, the Hispanic–White enrollment gap narrowed by nearly 10 points. This suggests that the policy successfully reduced barriers for Hispanic students.

The policy did not close the Black–White enrollment gap, and in fact, it widened slightly. While Black student enrollment increased by 5.8 percentage points, enrollment for White students increased by more (6.8 percentage points), so the Black–White gap actually grew by nearly 1 point; however, the increase was only marginally statistically significant at conventional levels (p-value = 0.12). According to DISD’s ongoing research, the gap narrowed in more recent years. The data suggest that fewer Black students met the eligibility threshold for automatic enrollment and that those who did were less likely to stay in the district or progress through advanced coursework.

Differences in academic eligibility and student mobility contributed to uneven effects across racial groups. 38% of Black students met the proficiency benchmark in 5th grade to be automatically enrolled, compared to 59% of Hispanic and 72% of White students, limiting their access to the policy.

Hispanic and White students were more likely than Black students to reach Algebra I by 8th grade, even if they were not identified for the accelerated track, indicating that clearer course sequences and more entry points could help reduce barriers to participation.

Figure 1: Algebra I Enrollment Before High School Increased for All Student Subgroups After DISD Implemented an Auto-Enrollment Policy

POLICY IMPLICATIONS

Automatic enrollment policies can significantly increase access to advanced courses. The increase in Algebra I enrollment before high school in Dallas ISD shows that setting advanced coursework as the default can successfully expand participation, especially when based on objective eligibility criteria. This supports continued use and expansion of opt-out models as a strategy to open doors for more students.

Equitable access requires more than changing the default to “opt-out.” Auto-enrollment policies should be paired with broader efforts to support students who have faced barriers to early academic success. While the policy increased access overall, it did not close the Black–White enrollment gap, and in fact, the gap slightly widened. This signals that eligibility thresholds tied to standardized test scores can perpetuate disparities for students who have faced barriers to early academic success, especially when alternative entry points into the honors pathway exist. Auto-enrollment policies should be paired with broader efforts, such as early academic supports, training for counselors, and family outreach, to ensure equitable outcomes as states like Texas move to scale these reforms statewide.

Investment in cross-district data sharing and coordination may be necessary to combat honors pathway attrition in state-wide implementation. One factor that contributed to the slight widening of the Black-White enrollment gap was a higher proportion of policy-eligible Black students leaving the district before 8th grade. This phenomenon can be improved with statewide implementation; however, states need to ensure that there is some level of reciprocity available for eligible students who transfer across districts. Disaggregated data should be used to regularly track enrollment and success rates by race, income, and other subgroups. Additionally, state education agencies should facilitate the sharing of these data and support districts as they work toward uniformly implementing auto-enrollment policies.

FULL WORKING PAPER

This report is based on the EdWorkingPaper “Closing the Gaps: An Examination of Early Impacts of Dallas ISD’s Opt-out Policy on Advanced Course Enrollment,” published in June 2025. The full research paper can be found here: https://edworkingpapers.com/ai25-1184

The EdWorkingPapers Policy & Practice Series is designed to bridge the gap between academic research and real-world decision-making. Each installment summarizes a newly released EdWorkingPaper and highlights the most actionable insights for policymakers and education leaders. This summary was written by Christina Claiborne.