Blake H. Heller

Nearly 10% of U.S. adults lack a high school diploma, limiting access to many jobs and postsecondary opportunities. For these individuals, high school equivalency (HSE) credentials, most commonly earned through the GED® test, serve as a primary “second-chance” pathway.1 However, most national evidence on the GED test’s educational value comes from cohorts in the 1980s–2000s, before test revisions in 2014 and 2016 raised academic standards and introduced “College Ready” designations intended to signal preparedness for college coursework. In light of these changes and substantial increases in both college enrollment rates and the share of jobs requiring postsecondary training, this study uses current, representative data to examine “How, and for whom does earning an HSE credential or a GED College Ready designation improve college enrollment, persistence, and completion?”

The bottom line: Modern GED graduates, especially those who are higher-scoring or motivated by educational goals, persist and complete college at higher rates than past cohorts. However, causal evidence suggests that barely passing the GED test or narrowly earning a GED College Ready designation has little impact on long-term college completion.

THE MODERN GED TEST

The GED test is the most common High School Equivalency (HSE) exam in the U.S., designed for people who did not graduate from high school but want a credential recognized as equivalent to a high school diploma. The GED test is made up of four subject tests (Mathematical Reasoning, Reasoning Through Language Arts, Science, and Social Studies), and students must score at least 145 on each test to pass. The study focuses on three key GED performance designations, which were introduced in 2016 to better align the GED test with college and career readiness standards and to signal college readiness beyond just passing the test. These designations are:

| GED Passing Threshold | GED College Ready (CR) Designation | GED College Ready + Credit (CR+C) Designation | |

| Score Required | 145 or higher on each of the four subject tests | 165–174 on a subject test | 175 or higher on a subject test |

| What it Means | The tester has demonstrated high-school level proficiency | The tester is considered “college ready” in that subject | The tester may qualify for college credit in that subject |

| Outcome | This is the baseline requirement to earn a state high school equivalency credential or diploma via the GED test. | Recommendation that colleges waive placement tests or remedial coursework in a subject for students who meet or exceed this score. | Some colleges may grant 1–3 credits per subject to students who meet or exceed this score. |

STUDY AND METHODS

Descriptive methods:

This study uses a representative sample of over 100,000 GED test-takers in 45 U.S. states between 2014 and 2023. The researcher linked test scores and survey responses to college enrollment and completion records to track outcomes such as college enrollment, persistence, and graduation over time. The study calculated descriptive statistics such as enrollment within one year, six-year completion, and conditional completion among enrollees and compared these to historical cohorts from the early 2000s and 1990s.

Causal methods:

To answer the question “Does earning passing the GED test (or earning a GED CR designation) itself open doors to college, beyond what a student’s test score or skills already indicate?” requires causal methods, and the author uses a regression discontinuity (RD) design to do this. Testers must reach precise score thresholds on a GED subject test to pass that subject test or earn a GED college readiness designation in that subject. This makes it possible to compare students whose scores fall just above and just below a given cutoff, two groups that are nearly identical in every way except for whether they earned the credential/designation. If students just above the cutoff go to college at higher rates than those just below, and the only meaningful difference between them is that one group earned the credential/designation, the difference in outcomes can be attributed to that credential.

For districts, states, and workforce agencies, knowing whether the credential is a true catalyst for postsecondary enrollment and persistence, or simply a marker of existing ability, can shape policy on testing, credentialing, and student supports.

KEY FINDINGS

Descriptive findings

- Today’s GED graduates enroll in college at similar rates compared to prior cohorts, but they are more likely to persist and graduate from college. These trends suggest that modern HSE credential recipients are using the GED test not as an endpoint, but as a springboard into postsecondary pathways.

- Enrollment: 43% of a national sample of 2003 GED graduates enrolled in college within seven years, nearly the same as the 44% seven-year enrollment rate in this study’s sample.

- Persistence: First-to-second-semester retention rose from 50% in the 2003 GED cohort to 79% among 2014–2016 GED graduates.

- Completion: In 2003, less than 12% of GED graduates who enrolled in college finished within seven years, compared to 22.6% of those from the 2014–2016 cohorts.

- College-ready GED graduates earned post-secondary credentials at rates similar to or higher than traditional community college students.

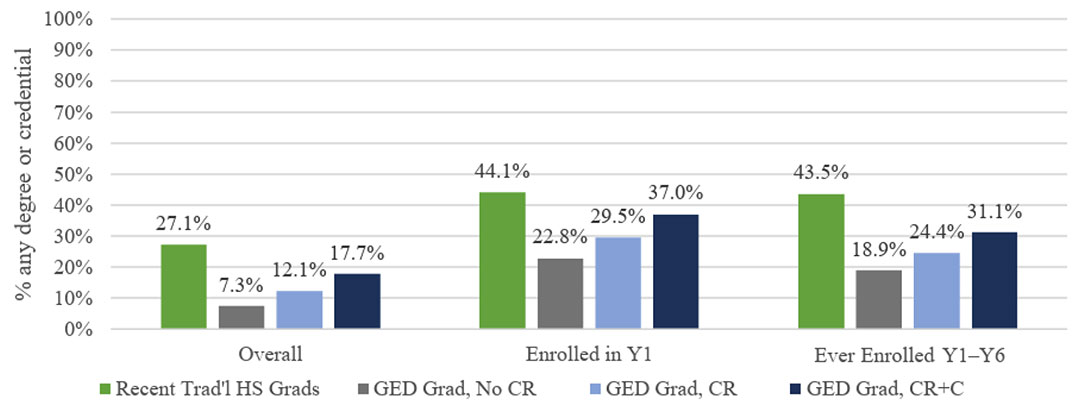

- Nationally, about 30% of community college entrants graduate within six years, compared to 30.4% of GED CR graduates and nearly 39% of CR+C graduates. Over time, many GED graduates also move into four-year colleges, and for the highest scorers, most of the degrees they earn come from those four-year schools.

- While many GED graduates, especially high scorers, do well in college, overall enrollment, persistence, and completion rates are still lower than those for traditional high school graduates.

- Students with higher GED subject test scores had stronger college outcomes.

- GED graduates who earned CR or CR+C designations had higher rates of college enrollment, persistence, and completion than those who did not receive these designations.

- Students who reported educational advancement as their primary reason for taking the GED test had better college outcomes than their peers with similar test scores. This points to motivation as an independent driver of postsecondary success.

- Among students who reported educational advancement as their primary reason for taking the GED test, more than 50% enroll in college within a year, nearly double the enrollment rate of GED graduates overall (27%).

- While only about 9% of all GED graduates earn a postsecondary credential within six years, nearly 33% of these educationally motivated students do so.

Causal findings

- Simply crossing the GED test’s passing threshold is not enough to drive long-term college success. While descriptive results show strong associations between higher GED subject test scores and better college outcomes, the causal estimates suggest that marginally earning a high school equivalency credential or GED CR/CR+C designation does not significantly improve postsecondary success.

- Passing Threshold: There was no causal impact on college outcomes for students who just barely passed a GED subject test compared to those who just failed.

- GED CR Threshold: There was no evidence that earning a GED CR designation causally increased enrollment, persistence, or graduation.

- GED CR+C Threshold: There was some evidence that earning a GED CR+C designation in Math or Social Studies boosts college enrollment and persistence, but there is no clear effect on completion.

Figure 1: 6-Year Completion Rates of GED graduates by GED College Readiness Level, Any Subject

POLICY AND PRACTICE IMPLICATIONS

- HSE pathways can be a meaningful on-ramp to higher education, but passing the GED test alone may not be sufficient for college persistence or completion

- The regression discontinuity analysis found limited causal effects of barely passing the GED test on long-term college outcomes, suggesting that an HSE credential alone may not shift trajectories without additional supports. Policymakers should pair HSE credentialing initiatives with college transition services—such as application assistance, bridge programs, and early advising—to ensure momentum continues after testing.

- State agencies, colleges, and workforce programs can use GED test performance bands to target advising, financial aid, and transition supports where they are most needed.

- GED CR and CR+C status strongly predict higher enrollment, persistence, and completion. These designations may help identify which students need less remediation and which require more wraparound support.

- Policies that award credit for GED CR or CR+C scores, waive placement exams, or streamline entry into credit-bearing courses can help these students move more quickly toward degrees.

- HSE credential holders may have diverse academic preparation levels; using GED CR/CR+C benchmarks can help identify those likely to succeed without remediation.

- Identifying and supporting educationally motivated learners could be just as important as boosting academic preparation.

- Students who reported “educational advancement” as their main reason for taking the GED test were much more likely to enroll and finish college, even controlling for academic readiness. Districts and adult education programs should integrate career/education goal-setting into GED test preparation and counseling to strengthen motivation and clarify postsecondary plans.

FULL WORKING PAPER

This report is based on the EdWorkingPaper “High School Equivalency Credentialing and Post-Secondary Success: Pre-Registered Quasi-Experimental Evidence from the GED® Test,” published in July 2025. The full research paper can be found here: https://edworkingpapers.com/ai25-1240

The EdWorkingPapers Policy & Practice Series is designed to bridge the gap between academic research and real-world decision-making. Each installment summarizes a newly released EdWorkingPaper and highlights the most actionable insights for policymakers and education leaders. This summary was written by Christina Claiborne.

1 GED® is a registered trademark of the American Council on Education (ACE) and administered exclusively by GED Testing Service LLC under license. This material is not endorsed or approved by ACE or GED Testing Service.